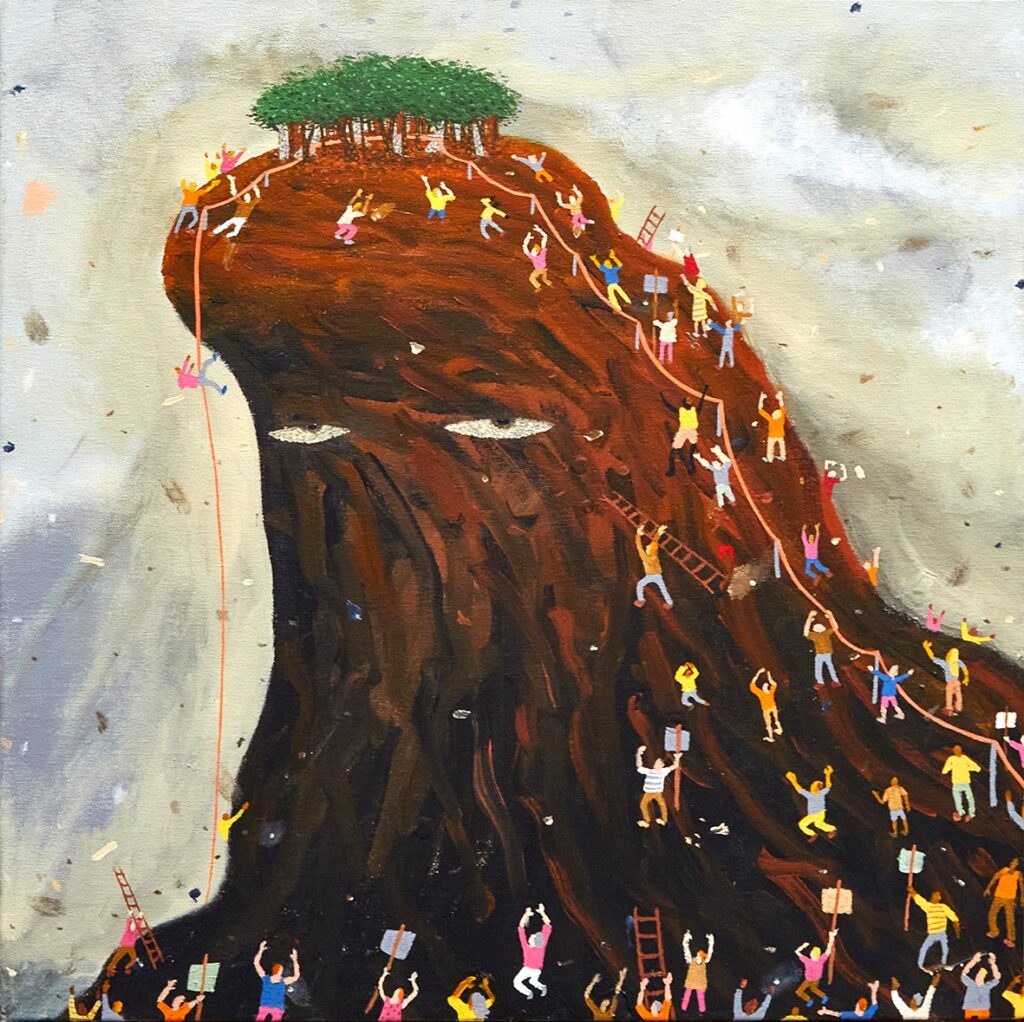

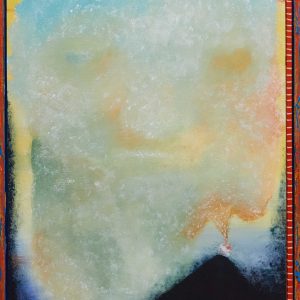

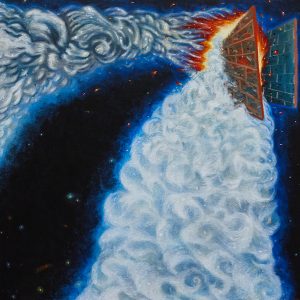

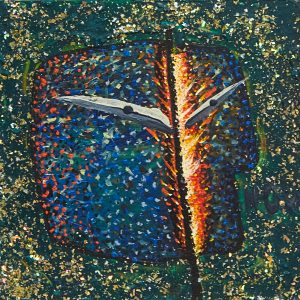

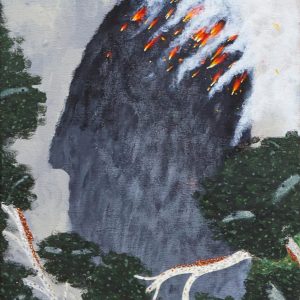

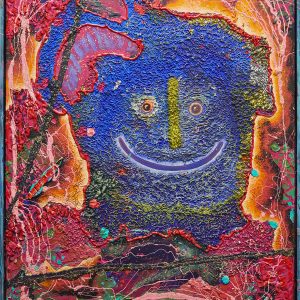

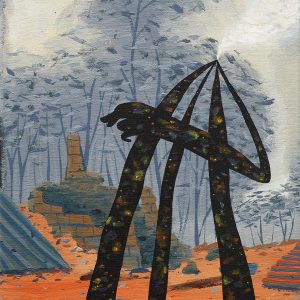

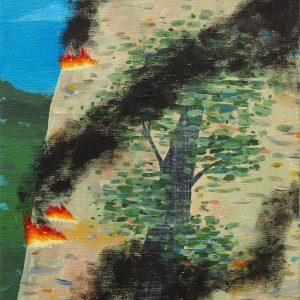

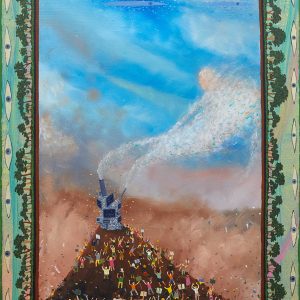

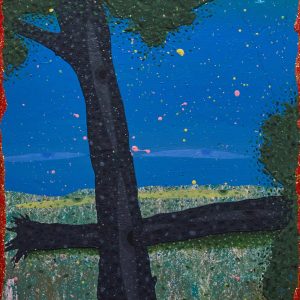

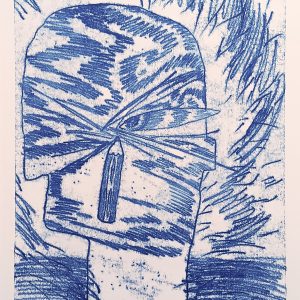

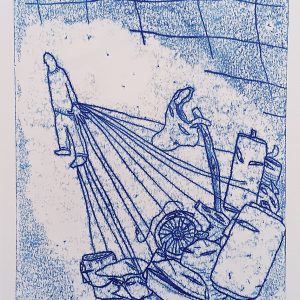

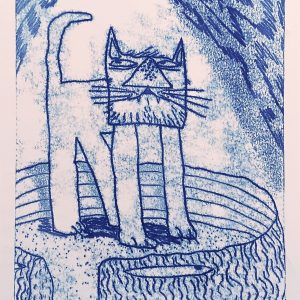

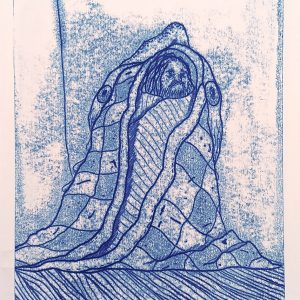

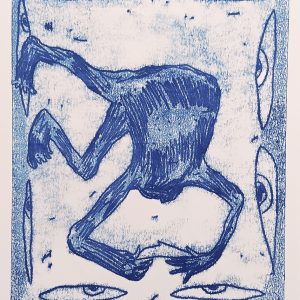

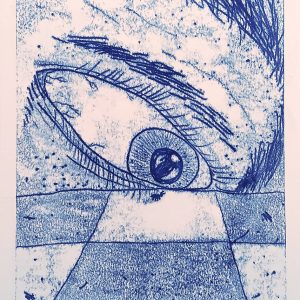

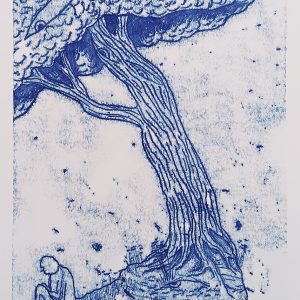

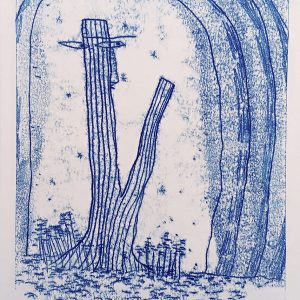

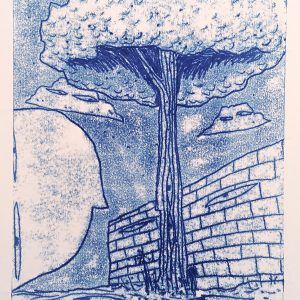

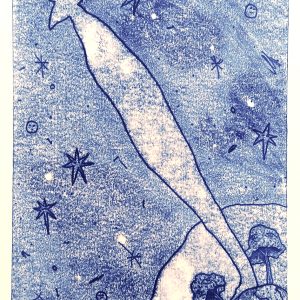

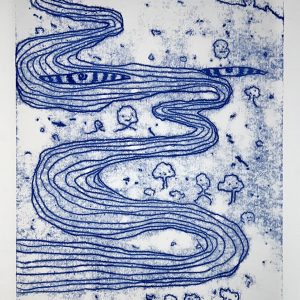

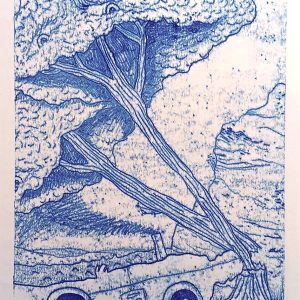

The unusual is a common sight in the paintings and monoprints of Dan Withey. In them, the ordinary is often made strange. A wind with eyes. A flower for a face. A human figure, part spider part man, drawing a miasma of the ether together like a folding of a handkerchief. The floating form of a tree hovering like a suspended boat in the air. What do they have to tell us? Things are alive.

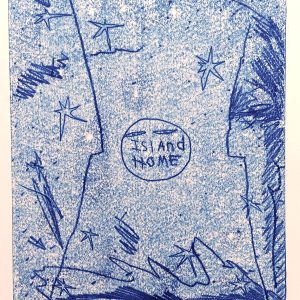

Withey’s recent body of work marks a shift in the artist’s practice. A return to study, after a long hiatus from formal education, has proved invigorating. Withey has always shown a hunger and curiosity to make sense of human existence – both his inner life but also the world at large – but in this body of work he has expanded the thematic preoccupation into a conceptual framework that has drawn together the disparate impulses and urgencies animating his practice into a singular focus.

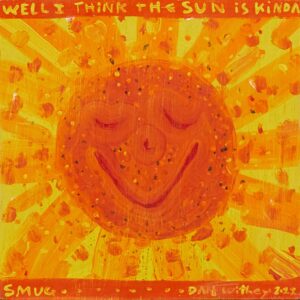

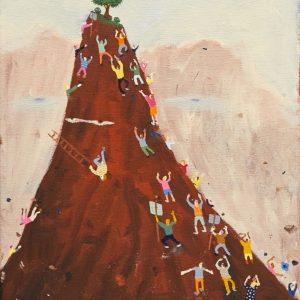

For a prolific maker, it’s an important juncture. An innate comedian Withey’s work has always carried a wry and sly humour. Attendant to the instinctive brightness, the dazzling colour and patterning, is a dark seam. Withey’s brightness feels like an unstable weather pattern. Looking at his work has a way of putting you in touch with the push and pull of cascading and conflicting thoughts. Those thoughts circle around ecological disaster and humankind. Human existence, or perhaps it’s just human exceptionalism, weighs heavily on the artist.

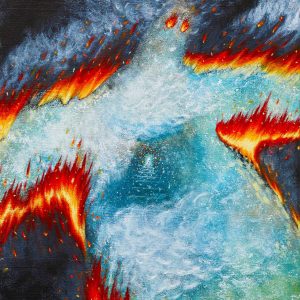

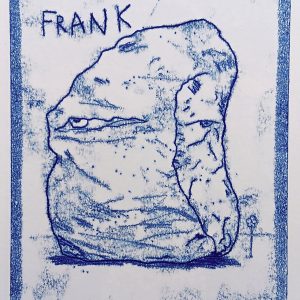

Withey has talked about the influence of animism on his worldview. The term animism, coined by anthropologist E.B Taylor in the 19th century, is derived from the Greek word anima, meaning soul or spirit, and animism meaning the belief in soul or spirit. Animism encompasses the belief that objects, sacred places, animals and natural phenomena possess a distinct spiritual essence. Used originally to describe ‘primitive’ cultures cosmology, for a century animism occupied the disciplinary boundaries of religion and anthropology. Viewed with circumspection, tainted by the ideals of colonialism, more recently animist ideas have been the subject of renewed interest in the humanities, social sciences and environmental/ecological movements and have been harnessed by First Nations Peoples in their efforts for increased self-determination. Animist beliefs shape and communicate cosmology, explain obligation, and frame relationship to place.

Modern science has framed humans are sentient subjects and the rest of the material world as inanimate objects. Instead of human dominion over the landscape, in animist cosmologies, humans live under the dominion of the landscape around them. Establishing relationships of obligation that tie humans to the land, and the land to the humans who live on it, animism foregrounds the inter-relationship of all beings, human and non-human.

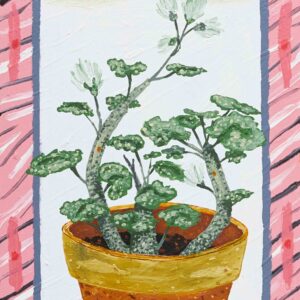

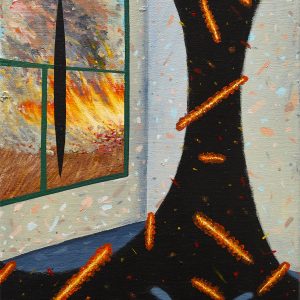

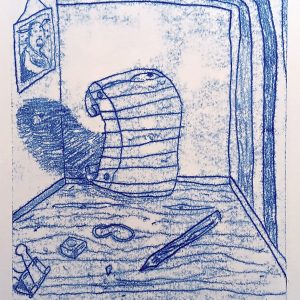

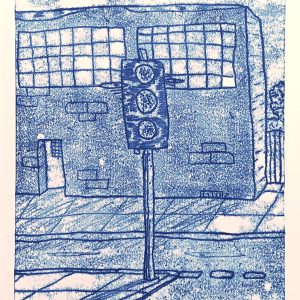

The presence of animals and plants in Withey’s artworks brings the relational into view. His hybrid creatures – part insect, part human – are often comic. Why they occupy interiors and create homes is one of Withey’s fantastic and somehow existential, conceits. Urban and domestic environments have a way of appearing symbolic and faintly absurd. Light fittings and vases, furniture and objects introduce an off-kilter mise-en-scene.

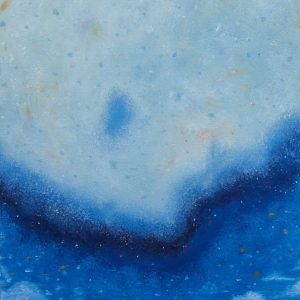

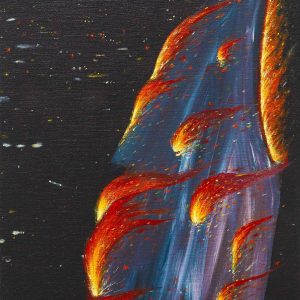

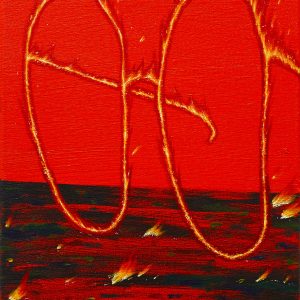

In Withey’s artwork, the world is dynamic and frequently unstable: it shifts and slides, collapses and refracts in unexpected ways. Compositionally, the works are active sites of negotiation in which opposing elements, figurative and abstract, co-exist. Converging lines and vanishing points create the illusion of space and depth but the coherence of the picture plane is always at risk of dissolving. Strong colours amplify this impression. Abundant decoration adds to the hallucinogenic effect. Withey’s paint splats and squiggles across the canvas in energetic and inquisitive loops replicating the erratic markings of beetles. Patterning erupts in all directions producing a density of surface.

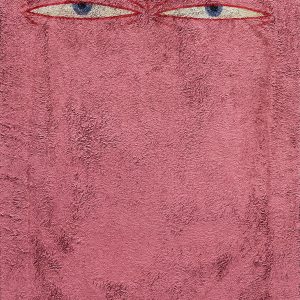

What these complex surfaces invoke is a threshold, one that invites speculation of the known and unknown, the seen and unseen, the spiritual and material. What of the eyes? In Withey’s work eyes are everywhere. Both figurative and abstract they inject a watchful presence, by turns protective and sounding alarm.

Anna Zagala, Associate Curator (Academic Engagement) at Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum